Sentinels launch: what next?

In the beginning of May, Greece and the European Space Agency (ESA) signed an “Understanding for the Collaborative Ground Segment Cooperation”. We were there.

In very simple terms, this means Greece can now receive data from the Sentinels – Europe’s Earth Observation satellites – in near real-time, thanks to a receiver antenna on its grounds. Greece will disseminate core information products locally and produce additional information products of its own.

Sentinel satellite data feeds into Copernicus – Europe’s ambitious environmental information hub. Copernicus was the subject of a lot of negotiations on its funding as a public European service. Many of those who have been working on it in one way or another (Eurisy included) popped the champagne last April 3, when the first Sentinel satellite was launched.

If negotiating and building Copernicus was hard, the next phase is possibly even harder.

If negotiating and building Copernicus was hard, the next phase is possibly even harder.

A Eurisy-moderated round table during the conference which marked the Agreement Signature between Greece and ESA hinted at challenges that lie ahead.

The round table gave the floor to users – local and regional authorities in Greece: the Corfu Region and the Ioanian Islands, the Region of Decentralised Administration of Macedonia, and the Interbalkan Environment Centre.

Greek Regional authorities are particularly effective at “absorbing” European structural funds to set up innovative projects, including for procuring geo-information. This ability is especially useful when facing the sort of budget cuts Greek administrations have been subject to.

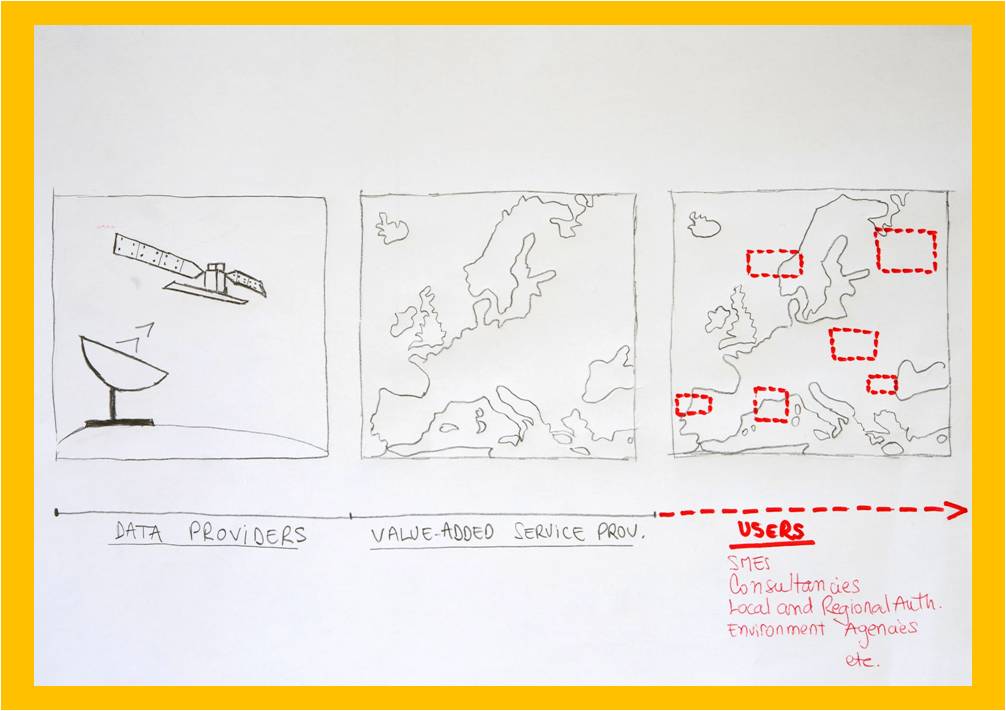

This positive end-user intermezzo in a conference otherwise focused almost exclusively on data provision (though to be fair, that was the purpose of the conference too) showed that professionals working on the “data” end of the spectrum are farther from “users” than usually assumed. There is a whole ecosystem of value-adders that turn data into information for a specific kind of user (an environment agency for instance), that in turn has another user (a regional authority for instance) and so on. The chain is long and everyone must do their bit for it to work out.

Each user has a very clearly defined perimeter of expertise. This means that each user can only work with specific types of providers, who are perfectly complementary in terms of size and expertise. If not, it does not make sense for either to work together. For instance, the Region of Macedonia (like most regional authorities in Europe), cannot process raw data in-house, so it needs a service provider who can. And not just a service provider who can process raw data, but also one who can neutrally select the best value-for-money proposition for the Region of Macedonia, from a range of different data sources/products available.

How well the chain works is about scale too. The National Observatory of Athens (which will be responsible for the Ground Segment in Greece) also has technical expertise and neutrality. But would it have the resources to provide geoinformation services to all regional authorities in Greece, at that level of detail? Doubtful. Which is why the existence of intermediary users/service providers – like a Regional Environment Centre – seems to make sense.

And so the real challenge ahead lies not in launching additional Sentinel satellites – though that is a feat in itself of course. The real challenge is in how well connected and “irrigated” the downstream part of the value-added chain is. Is everyone in place for the chain to work out?

This leads us to the thought of how to define a user. Is there more than one definition? And which users should the space community concern themselves with? But that will be the topic for a different post.